How High the Moon

“How High the Moon”

Is the name of the song

How high the Moon

Though the words may be wrong

We're singing it because you ask for it

So we're singing it just for you

How high the Moon

Does it touch the stars

How high the Moon

Does it reach out to Mars?

Black Rudy joined them at their table after the song was over. "Did you enjoy the show?" he asked.

He pulled out a cigarette and offered it to Ellas. Ellas took it and spun it on his fingers. “The Tippin’ Inn has the best music anywhere.”

"C'mon outside with me for a minute," said Rudy. "I want to show you something."

The two men walked outside into the cold night air. Rudy gestured for Ellas to follow him behind the bar. Ellas looked back through the open door, then closed it behind him and followed Rudy.

There was small trap door leading down to a cellar. Rudy opened the door. Dave followed him down into the darkness, and then lit a match.

Rudy switched on the lights. The cellar ran the entire length of the bar. There were at least 10 tables with just as many chairs around each table. But what caught Dave's attention was the printing press in the corner.

On the walls were posters with hammers and sickles. Ellas knew what Rudy was going to say before he said it.

"I guess something happened with the hammers and sickles," said Dave. Rudy nodded and they sat down to enjoy their cigarettes.

The Tippin' Inn

It was the height of the Cold War, and a big sign off Route 73 in Winslow Township, Pennsylvania once directed music lovers into what seemed like just a wooded area with a few houses. But several blocks back, there was a seminal source of entertainment for mid-20th century African Americans, who often were excluded from mainstream events.

"Back in those woods was my Daddy's Tippin' Inn," said Helen Toomer Beverly, 76. "You turned off 73 and within a block, you could hear the music and smell my mother's fried chicken. Buses would come from Philadelphia and Atlantic City. It was the chicken-and-chitterling circuit, but, boy, there were a lot of people having a good time."

They called that section around Winslow and the tiny town of Chesilhurst and part of Berlin, "East Berlin." It was an enclave where blacks settled during the early part of the last century, like Lawnside near Haddonfield and what was known as Matchtown near the Merchantville/Cherry Hill/Pennsauken border.

Beverly's father, James Toomer, came to the area as a young man in the 1930s, and opened the club. The Tippin' Inn was the setting for one of my father's short stories called How High? and serves as a recurring symbol for the communist underground in the 1950s throughout his collection of stories. The silent revolution. The rise of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie. The bloodless revolt. The Brotherhood. Ralph Ellison. The Invisible Man. These were all inspirations for my father, Dave Eskey, with his protagonist, Dave Ellas, making an appearance in five out of eight of his stories. Joseph Heller was his editor, another writer who was heavily influenced by the Cold War.

In a 1977 essay on Catch-22, Heller stated that the "antiwar and antigovernment feelings in the book" were a product of the Korean War and the 1950s rather than World War II itself. Heller's criticisms, apparently, are not intended for World War II but for the Cold War and McCarthyism instead. He went on to write several other novels, but none receiving the same critical acclaim as Catch-22. His anti-hero, Robert Slocum in Something Happened, represents a certain type of nameless, faceless Cold War victim - the man who rejects the call of the communists, and is forever stymied in his life and career. The Biblical King David in God Knows is a similar character, one who is forever disappointed in life, watching helplessly as his wife and son jockey for his throne and plagiarize his psalms.

This historical collection of short stories provides a glimpse into an earlier era and begins to define a language for today's Cold War: White Coke, Red Peppers, the Hammer and Sickle, the Brotherhood and CCCP are still relevant symbols for the silent underground of extremist groups financed by foreign powers in America. My tentative title for the collection is A Perfect Catch: The Dave Ellas Series.

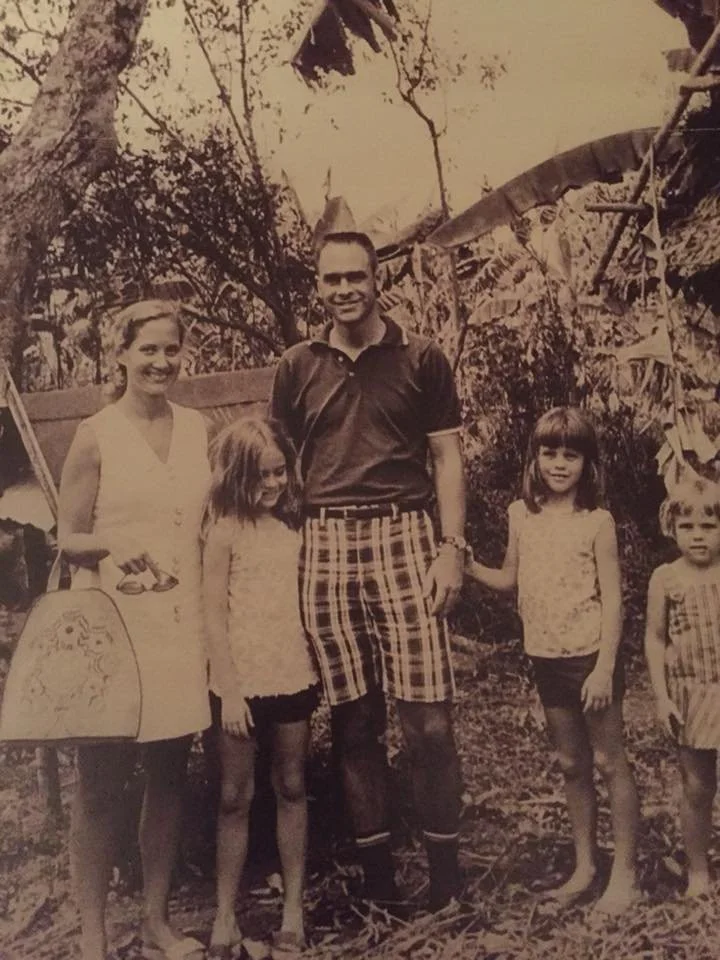

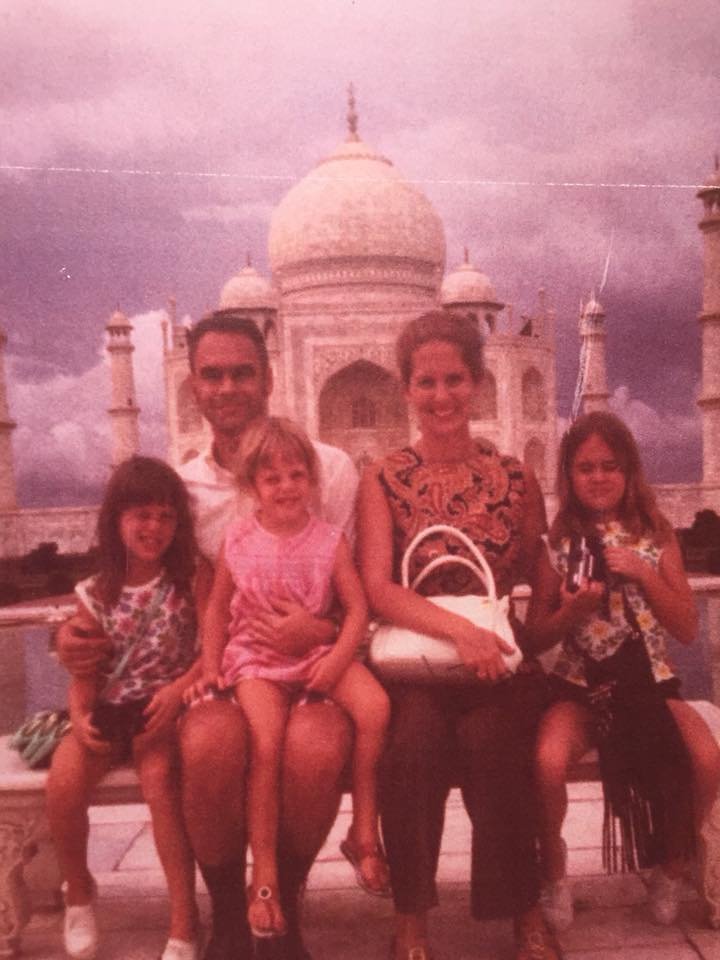

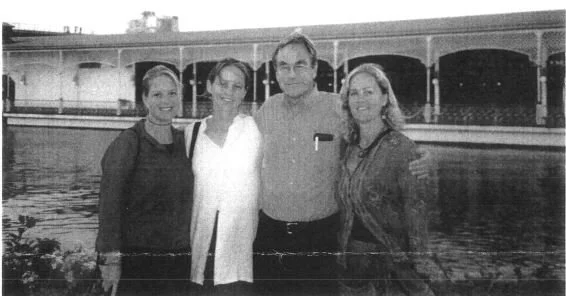

My father went on to have a long and distinguished career in academia after writing his short stories, ending as full professor of linguistics and the Program Director at the MSTESOL Rossier School Education at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, also my alma mater. We lived and traveled all over the world in the 1960s, including Beirut, Lebanon at the same time as Kim Philby, a key member of the Cambridge Five Soviet spy ring, and his wife Eleanor, and Bangkok, Thailand during the Vietnam War.

Because of the GI Bill, a federal program that helped tens of thousands of veterans to pursue higher education following the war, Heller was able to enroll at the University of Southern California in 1945. He published his first short story in the prestigious Story magazine that year and was married to Shirley Held, with whom he eventually had two children, Erica Jill and Theodore Michael. The next year, he transferred to New York University.

A Perfect Flower

The apartment was wide and low-ceilinged and furnished in the best taste; and the wall beyond the piano was nearly all glass, one great window opening on the New York City sky fourteen floors above the avenue. She sat down at the big piano and tried to play.

Just then the door from the tiny vestibule eased open and the maid slipped into the room carrying a full bunch of long-stemmed pink sweetheart roses wrapped in waxed cellophane.

"I think roses are the perfect flower," Mrs. Merriman said, beginning with infinite care to trim the long stems so that each stem might hang even from the cellophane. "As long as there are a few roses in a room, it just can't be bare. Eloise, don't you..."

But Eloise was gone.

She walked across the room, and lifted the tall old vase perched brittle and thin-necked on the piano. She took the wilted flowers from the vase, golden butterscotch roses, Rose Zanzibar, and exchanged them for the new ones. She wrapped the dead roses in cellophane and set them aside on the small end table by the window, the one with the broken leg. Finically, she arranged each long stem, careful not to jag herself on the thorns, placing each into its space beside the next, preparing as best she could a splendid little pink cloud of roses.

Eloise was a nice girl, but definitely a little dull. Then again, it was probably no great wonder. She could picture Eloise living in one or two rooms with her father, who was probably a janitor or some such thing, and a fat mother and about twenty brothers and sisters, and all of them doggedly drudging at terribly monotonous jobs just to earn enough to go on living, if you could call that sort of thing living. If Eloise were a little dull, well perhaps you couldn't really blame her.

She suddenly remembered the dead roses on the broken end table in the corner by the window. It was a good table with a glass top, but the broken leg made it unstable. Maybe Eloise would like it.

She took the cellophane-wrapped roses back to the kitchen and threw them away. Grasping a hammer and a box of nails from the toolbox, she walked back to the music room, and placed them carefully on the glass tabletop. If Eloise could fix it, she might as well have it.

The apartment was awfully quiet these days. If only Meg were here again. Dear little Meg; she was the best daughter anyone could have asked for. Little Meg - curly head full of the endless unfortunate questions of an eight-year old, heart full of wonder and bright young dreams. Perhaps every one of her dreams would come true. Perhaps one day she would fly as high as the whooper swan or the bar-headed goose. But maybe that wouldn't be the best thing. Then she might fly away from home.

Later that day, expecting Mr. Merriman's return, Mrs. Merriman placed two matching candelabras on the table in the tiny vestibule. She lit each of the eight candles and then lay his matchbook from the Tippin' Inn beside them. She heard the front door open behind her and turned around to face her husband.

The breeze from the open doorway blew into the room but the candles did not blow out.

“Can you believe that wind?” He said as he took off his hat and shook it out.

And then he saw the matchbook.

Worried Man, Worried Song

Something stirred in the cellar doorway over at the side of the prescription counter. A moment later, Barry Lewis stepped out of the doorway and made his way over in the dark to the other side of the soda fountain. He explored the space under the counter with a touch of a small boy's curiosity and then he found his guitar.

Barry reached into his pocket and pulled out a matchbook from the Tippin' Inn. He lit the last match, and held it up to the empty packet. It caught on fire and he tossed them both into the trash bin. The bin started crackling and smoking and he walked out of the empty soda shop, with his guitar strap slung over one shoulder.

Run, Bobby

Johnny squirmed around in his seat at the back of the room. He looked out the window over to the practice field, covered with dirty snow now. He'd thought about it before. He would probably never play ball there again. He still remembered that time when he and Fabian had come across a dead falcon lying in that field, and the shivers he'd felt when they'd picked it up and carried it over to the trash cans. Probably planted there by another team, but it left him with an uneasy feeling anyway. Some grade school kids were out there on the field in the snow throwing some other kid's hat around. He remembered one scrimmage in his junior year, just kneeling over there when out of nowhere Big Al calls him up and puts him in at left half for Joe Orvich who was slow as hell.

The bell rang, finally.

Al Paulak looked up from his desk. "Hi, muscles," he said. "What's on your mind?"

"Hi, Coach, " Johnny said. "I was just wondering if that guy from Miami was here yet."

Al swung around on the straight-backed chair. "Yeah, he was here. Still is as a matter of fact. He's up in the gym talking to Bono."

"How was it? You do any good?"

Al looked down on the list of letterman. "I don't know, Johnny," he said. "Same old gripe - too small. Sorry. But we'll keep trying."

Big Al was sorry too. He was trying to grin and look as though there was still a chance and all of that. He was really trying. Everyone around there really tried. It was probably great. He could still hear Big Al yelling, "Run Bobby, run Bobby, run, run, run...!" But he wasn't running anymore. Johnny shrugged his shoulders.

This is feedback from Robert Hess, one of my father’s classmates. This story came with a long list of comments from other students. Joseph Heller's feedback on A Perfect Flower was generally positive and supportive, and I suppose his introduction of my father to his literary agents was indicative of encouragement. However, I can't understand why the stories were never published. With connections at Simon & Schuster, and a wide network of influential friends and colleagues, Heller was well positioned to open doors for his former student in the New York City literary scene of the 1950s.